Introduction

More than doubling the power output of a steam locomotive while simultaneously cutting fuel consumption by 25% is the surprising achievement of one current steam development programme. This fascinating story and the background leading up to it is the topic of this article.

The need for more powerful locos

The railway in question is the nine mile long Bure Valley Railway running between the historic market town of Aylsham and Wroxham 'the Capital of the Broads'. This 15" narrow gauge line is a major tourist attraction carrying over 130,000 passengers a year and runs on the former Aylsham extension of the East Norfolk Railway. The track bed was originally laid as a standard gauge line in 1880 but after closure in 1982 was relaid as a 15" gauge tourist railway in 1990 at a cost of £2.5m.

As a volunteer engineman weaned on the continuous gradient of the Festiniog Railway in North Wales I was at first surprised to find that the line is very demanding for both locomotives and engine crew. However, all becomes clear when you assimilate three key points. Firstly, when the line was constructed the earthworks involved were kept to modest proportions and thus the line follows the gentle undulations of the landscape. This translates in railway terms to a series of switchback banks in the range 1 in 100 to 135 which are too long to rush giving little respite in either direction and with one short section of ¼ mile at 1 in 76.

Secondly, with a maximum line speed of 20 mph and a start to stop average of 12 mph involving three intermediate stations this is no stroll in the countryside. In fact it is more akin to a fast suburban service which demands rapid acceleration with top speeds close to the permitted maximum to maintain time. Thirdly, train loadings have been inexorably creeping upwards and the summer service regularly brings 12 bogie carriage plus brake van formations of around 40 Tonnes gross weight or four times the weight of the locomotive to put it in perspective.

Initially the line was operated by locomotives hired from the Romney, Hythe and Dymchurch Railway but as traffic grew it became clear that the greyhounds from the flat Romney Marshes were being asked to work outside their comfort zone and something larger was required.

The ZB is born

As a result the first two of the ZB class of locomotives, BVR Nos. 6 and 7, which are based loosely on the Indian Railway type, were designed and built very cost effectively by Winson Engineering in 1994. The class has become closely associated with the line and in service the new locomotives quickly established themselves as rugged and reliable performers. They have served the railway extremely well and with a maximum tractive effort of 3054 lbs are capable of starting the heaviest of trains even in adverse conditions. In traffic however, the fuel and water consumption was found to be high. Although initially this was not a serious issue, as passenger loadings continued to rise over a number of seasons it became apparent that the locomotives were slow to accelerate the increasingly heavy summer loads and could not maintain full line speed on gradients.

Operating the locomotives at the edge of their performance envelope trip after trip was a challenge for crews especially if single manned. Every gradient had to be rushed at full line speed with as much water in the boiler as you could manage, the pressure on the red line and then with raucous roaring exhaust the speed would slowly and inexorably burn off despite your best efforts. With a heavy 12 coach train the speed would settle to around 12-15 mph at 50% cut-off and then all you could do was watch the water go down and hope the fire held out until the end of the climb as any attempt to fire while pulling would precipitate a disastrous loss of pressure. With the top of the climb behind you the cut-off could safely be shortened and with both injectors on to replace the water the train would be worked up to line speed again on the down grade. Getting a large round on the fire was the next essential item and as the doors opened an absolutely white incandescent fire would greet you. The trick was to keep it thin enough to burn really hot in the climb but not so thin it burnt right through to form a hole. Normally there would be some latitude in the optimum firebed thickness but at this level of evaporation there was only one option, perfect every time. Of course perfection is hard to achieve and there was no way to recover from errors of judgement, you just had to live with the consequences for the rest of the trip! Coal deliveries were serious events as each new batch had the potential to turn a difficult tour de force into impossibility. Only 'rocket fuel' was acceptable, loads of Welsh with hints of slate were sent away with baleful glares and any vestige of slack was shovelled to one side as it would simply be thrown out as red hot grit if you tried to fire it.

The voracious appetite for fuel of the ZB led to them being dubbed 'the miners friend', because you never stopped shovelling. Typically a 3 trip 54 mile day plus lighting up would require the tenders to be heaped up with up to 35 buckets of coal weighing approximately 410Kg. One enthusiastic driver was sure he had got this fuel economy thing licked and loading only 28 buckets at the end of the previous day resulted in an emergency call for coal to be despatched to meet him on route to enable him to get home!

The first BVR improvements

In 1997 2-6-2T BVR No. 8 entered service having been erected from a kit of parts supplied by Winson Engineering in the BVR workshop at Aylsham. Although this locomotive is styled to resemble a Vale of Rheidol Tank it is also a member of the ZB class sharing the same chassis, cylinders, running gear and boiler with only superstructure changes creating the visual transformation. One important difference was that unlike other members of the class it is oil fired which is useful in the dry summer periods if fire risk is high.

About three years after Nos. 6 & 7 entered service the BVR investigated the valve gear design and discovered that the piston valves had a massive 10mm of exhaust clearance which allowed the steam to be exhausted from the cylinders before it had expanded adequately. New valves were manufactured for No. 6 and as a result the locomotive performed better and coal consumption fell by 20%, typically to around 27 buckets of coal per day weighing approximately 320 Kg. Subsequently these improvements were also applied to Nos. 7 & 8 with some further small experimental differences between the three locomotives.

At first the reduction in fuel bills and the slight latitude created by the lower evaporation rates was reassuring. However, the need to still push the locomotives hard with no quarter given was exacting a toll as the high fire temperatures were shortening the life of the boilers and repair costs were rising seriously.

No. 9 'Mark Timothy' arrives

In 1999 the class expanded to a total of 4 with the arrival of 2-6-4T, 'Mark Timothy', BVR No. 9. It is named in memory of owner Alan Richardson’s son and originally it was styled to resemble a County Donegal Class 5A locomotive.

When it was first delivered a number of serious problems were identified and the locomotive was returned for rectification. When it was redelivered, it was apparent that it was still unable to enter service, and shortly afterwards Winson Engineering closed down.

Rebuilding a brand new locomotive before it enters revenue-earning service is an unusual step to have to take but as there were a number of serious technical issues to be resolved Alan Richardson consulted locomotive builders Alan Keef Ltd, who undertook to rebuild the locomotive in 2001.

At this point the scope of the problems was rather daunting. An immediate issue was that the cab was too low to accommodate the locomotive crew as even the shortest engineman couldn’t sit upright. There were also a large number of detailed mechanical problems with the frames and motion which would have prevented reliable regular use. The oil firing system was not functioning properly and indeed the trials at Perrygrove had to be undertaken with temporary firebars and a coal fire. Lastly there were a number of areas on the boiler which required remedial work to satisfy the boiler inspector before he would sanction use other than for test purposes.

A key issue was to steam test the locomotive before stripping it and arrangements were made with Michael Crofts for these trials to be undertaken at his Perrygrove Railway when there was no passenger service running. These trials proved very useful and despite the problems, the locomotive was shown to have significant potential.

Remodelling the locomotive

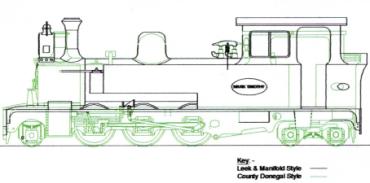

The locomotive then moved to Keef’s works at Lea Line near Ross-on-Wye and stripping of the locomotive commenced. In parallel a design study was carried out to look at the options to overcome the limited room available in the cab. It became rapidly apparent that the County Donegal prototype around which the external appearance of 'Mark Timothy' had been modelled was very restrictive and that the visual balance of the locomotive would be spoilt if an enlarged cab were to be fitted. As an alternative, discussions between Alan Richardson and Patrick and Alice Keef settled on the possibility of changing the appearance to match that of a Leek and Manifold locomotive.

This had the benefit of providing a much larger cab but pushed the limits of the current BVR loading gauge especially in terms of clearance between both the cab roof and chimney and the top of the tunnel at Aylsham.

In conjunction with the BVR it was arranged to measure in detail the vertical clearances in the tunnel and also to check the effect on draughting of the fire with the top of the chimney close to the roof.

These tests were undertaken in April 2002 and with No. 7 sporting a temporary extension to the chimney several runs were made through the tunnel at a variety of power levels to see whether there was any tendency for the fire to blow back into the cab. The trials were a success and with all eyebrows still intact it was agreed that the revised overall height was practical.

With a major remodelling exercise to be undertaken it was also decided to change the locomotive from oil to coal firing. This would reduce both fuel costs and the ambient noise level for engine crew as oil firing tends to produce high levels of low frequency noise particularly when working hard.

The article continues with part two: The New Front End.